Church Building Stone

Dr Nigel Woodcock, Emeritus Reader of the Department of Earth Sciences at Cambridge University, and Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge has surveyed the building stone of St Andrew's and given us permission to publish his working notes and the following summary of his findings. Click on the picture above to open his notes in a new window.

The stones used

St Andrew’s is typical of medieval churches in being built as far as possible of locally available stone. The motive for this choice was economic. Until the coming of the railways in the mid-19th century, every 10 miles of overland transport cost as much as the stone cost at the quarry gate. There are three main sorts of local stone in the church and one local brick variety:-

Clunch – harder parts from the local Chalk Group, a very fine-grained limestone of late Cretaceous age. One horizon suitable for building is the Melbourn Rock, which was quarried at Limekiln Hill, Cherry Hinton, about 4 kilometres north-northeast of Stapleford. Softer Chalk was quarried at Little Trees Hill, less than 2 km to the northeast.

Fieldstone – cobble to boulder sized lumps of stone that were collected from surrounding fields. They would be ploughed up and moved to field margins, particularly as new areas of arable land were tilled. The stones are of a variety of different rock types, moved to the area by Quaternary ice sheets and associated rivers. Fieldstone typically comprises ovoid lumps, but also more irregular pieces of Flint.

Flint – a hard, siliceous rock that originated as irregular lumps (nodules) within the upper Chalk Group limestones. Flint is typically dark grey or black on broken surfaces, but nodules have a white skin around them on unbroken lumps. Since late Cretaceous time, the resistant flints have been progressively weathered out of the Chalk and transported by rivers or ice. They form a common and distinctive component of fieldstone.

Gault brick – a fired product of the Gault Formation, clays of early Cretaceous age that occur extensively west and north of Cambridge. Gault bricks are typically light yellow to pink and were first used in Cambridge in the early 18th century. They were produced at numerous local brickyards during their peak popularity in the 19th century.

Fieldstone and flint are unsuitable materials for fashioning buttresses, quoins (corner stones) and other exposed dressings. Clunch is too soft to last long in these positions. Therefore, durable and workable stone had to be imported from further afield. St Andrew’s contains stone from at least four quarries in the Lincolnshire Limestone Formation of mid-Jurassic age. The nearest source of this stone is in the Stamford area, about 100 kilometres to the northwest of Stapleford. The prohibitive overland transport costs for this stone were avoided by shipping the stone by inland boat, a transport mode costing five times less than overland transport.

Barnack – a limestone dominated by shell fragments and also containing 1 mm diameter spherical carbonate grains called ooids. Barnack, 5 km east-southeast of Stamford, was the main Lincolnshire Limestone quarry exporting stone beyond its local area from Roman times until the quarries were worked out about 1460. Having been exposed to the Stapleford climate for at least 550 years, Barnack has typically been weathered along the original sedimentary bedding surfaces to give an etched appearance.

Ketton – a limestone composed entirely of 1 mm sized ooids. It was exported from the quarries 6 km west-southwest of Stamford from the early 17th century.

Casterton/Stamford – a limestone similar to Ketton, but with some fine-grained shell fragments. One source is the 19th century Casterton quarries, 2 km to the northwest of central Stamford, but similar stone was available from numerous small quarries in and around Stamford from an earlier date.

Clipsham – a limestone with a higher content of shell fragments than Ketton or Casterton, with coarser variants looking similar to fresh Barnack. Clipsham quarries, 10 km northwest of Stamford, were opened by the Romans but the stone was never as popular as Barnack. It has only been used in St Andrew’s in the 20th century and is one of the few Lincolnshire Limestone varieties currently available.

Finally there is one limestone imported from nearly 300 kilometres away:

Portland Whitbed – this almost pure white limestone contains ooids, carbonate mud and fine shell material, but also bivalve mollusc shells some centimetres in size. It comes from the Isle of Portland in Dorset, and arrived in Cambridge in the 18th century. It was not used in St Andrew’s until the 20th century.

The outside of the church

We now take a geological walk around the outside of the church, starting at the western tower, and working eastward.

|

|

|

Tower west window

|

|

Tower south belfry window

|

|

C14 yellow Barnack and partly repaired white Clunch. Set in a C14 wall of fieldstone/flint rubble with Clunch and Barnack ashlar (smoothed blocks) |

|

C14 Barnack sill below 1803 Gault brick jambs and arch, probably replacing C14 Clunch |

|

|

|

|

The tower, said to be 14

th century, has rubble walls, predominantly of

Flint but with some other

Fieldstone and blocks of

Barnack and

Clunch. The plinth, buttresses, quoins and window sills are

Barnack.

Gault brick has been used to repair the buttresses and to replace most of the belfry and mid-tower windows, probably during the 1803 renovation. The west window has

Barnack sill, mullions, arch, hood mould and outer jambs. However,

Clunch survives in the tracery and inner jambs, as a reminder that

Clunch would have been the dominant stone in every other medieval window, now replaced.

|

|

|

South aisle

|

|

|

|

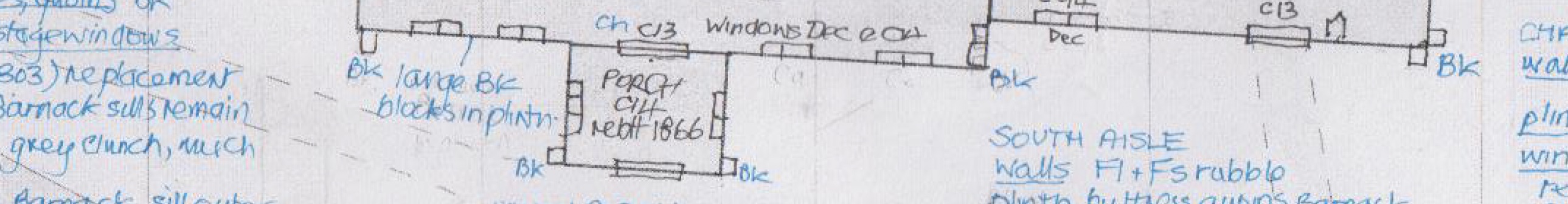

C13 Fieldstone/flint rubble wall with Barnack in the buttress and as very large blocks in the plinth. Window restored 1866, possibly Casterton |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The 14

th century aisles and south porch, and the 15

th century north chapel all have rubble walls, mostly of

Flint and other

Fieldstone. There is a significant patch of white

Clunch in the western wall of the north aisle. The plinth, quoins and buttresses are

Barnack, including some very large blocks in the south aisle plinth, west of the porch. The windows have mostly been replaced in what is probably

Casterton during the 1866 restoration of W.M. Fawcett.

Barnack sills survive in the west window and the middle north window of the north aisle, in the east window of the south aisle, and in the chapel windows. The

Casterton stone probably replaces original

Clunch, which would have been badly weathered by the 19

th century.

The vestry, built in 1925 and extended in 1978, has walls of Flint-rich rubble on a plinth of Gault brick. The quoins, door and north window appear to be of Clipsham, but the small east window is of Ketton.

|

|

|

Chancel south

|

|

|

|

C20 Portland Whitbed ashlar wall replacing C13 local Clunch, over fieldstone/flint rubble plinth. Windows mostly C20 Clipsham repair. Door with C13 Barnack plinth and Clunch inner jambs then possible 1873 Casterton repair of outer jambs and arch |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The 13

th century chancel originally had

Clunch walls on a rubble plinth, but the

Clunch was replaced by

Portland Whitbed in the 1970s. The windows seem to be a shell-rich

Clipsham but with some surviving parts of original

Barnack, newly dressed to match the

Clipsham. The south door has a

Barnack plinth to the jambs. The inner jambs are original

Clunch, but the outer jambs have been replaced by

Casterton.

The inside of the church

|

|

|

Norman chancel arch

|

|

|

|

Entirely in Barnack limestone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Moving inside the church, much of the stone is obscured by render and, or, lime wash. The piers and arches of the early 14

th century aisle arcades are of

Clunch, which is not subject to the weathering that would degrade it externally. Also of

Clunch are the internal frames to the windows, certainly in the chancel and probably elsewhere. However the fine Norman chancel arch is of

Barnack, as is the 13

th century font.

Summary

In summary, St Andrew’s, Stapleford is a typical example of a southern Cambridgeshire medieval church, originally constructed of local Fieldstone, Flint and Clunch, with imported Barnack stone used for exposed external dressings. The rubble walls were probably originally rendered like the tower at St Mary’s, Great Shelford, but also limewashed to give the appearance of the present Portland stone chancel. The render would have been removed by the mid-Victorian restorer, William Fawcett, who mistakenly thought he was returning the church to its proper medieval appearance.