Church Monuments

Nicky West, a member of the congregation at St Andrew's, investigated our church monuments and wrote the following articles originally published in The Stapleford Messenger in November & December 2021:

Part 1

Memorials in St Andrew’s and contested heritage

Our beautiful church has several memorials and stained glass windows which commemorate deceased people who went to St Andrew’s. They have been untouched and unquestioned for many decades.

But following last year’s brutal police murder of African-American George Floyd and global Black Lives Matter protests, the Church of England has asked all its churches and cathedrals to review their “contested heritage” – or the memorialisation of people or events connected with racism and slavery which can be seen as “symbols of injustice and a source of great pain for many people” (Historic England).

But it all happened so long ago! Why does it matter?

It matters because many minority ethnic communities still face discrimination and some of the anger felt is directed towards material culture glorifying people who were a part of this in the past. It’s important to acknowledge this, start a dialogue and where possible, take steps to redress the hurt caused.

I concentrated on the memorials dating from the 19th century (although the slave trade was abolished in 1807, slavery itself continued in the British Empire until 1833). I did not look at the smaller memorials in the Baptistry, which date from the 20th century; nor did I look at the stained glass window (in the south aisle chapel) dedicated to Eivira Bidwell, who died in 1959.

Lady Charlotte and Sir George

The largest memorials in St Andrew’s are in the Lady Chapel, and are dedicated to Charlotte Elizabeth, Lady Godolphin Osborne, and her son, George Godolphin Osborne, 8th Duke of Leeds, and his wife Harriet.

Family wealth rooted in land

The Godolphin Osbornes were wealthy. Four centuries of strategic marriages had seen them acquire landed estates, properties and titles across England, Scotland and Wales.

By 1883, these estates together added up to 24,000 acres – roughly the same as eight Wimpole estates! They brought in an income worth, in today’s money, £4.2 million.

In addition, the Godolphin Osbornes controlled the leases on a number of Cornish tin mines which were another important revenue source.

Without going through their papers (of which there are many held in county archives across England and in the National Archives), it looks like their wealth came from farming and tin-mining in Britain. I could not find any evidence that their wealth came from the proceeds of slavery.

A liberal family with a social conscience

In fact Charlotte Elizabeth’s husband and younger son were both ardent reformers. Her husband was Lord Francis Godolphin Osborne, Member of Parliament for Cambridgeshire between 1810 and 1831.

A Whig (Liberal) by temperament, he regularly presented petitions on behalf of constituents before the House of Commons for reduced taxation on “the necessities of life”, revision of the criminal code, parliamentary reform, poor relief and anti-slavery petitions. He also attended local meetings to support the abolition of slavery.

Charlotte and Francis’s son, Sir George Godolphin Osborne, inherited the Dukedom in 1859 when the 7th duke (Sir George’s cousin) died without issue. He seems to have led a quiet life at Wandlebury, unlike his younger brother Sidney, who for over 40 years was a passionate correspondent to The Times, writing hundreds of incendiary letters pressing for reforms in healthcare, housing, agricultural labour, education and poor relief, which delighted and enraged readers at the same time. Although I couldn’t find any letters on slavery, he stood up for other marginalised groups including Irish tenants and women.

Memorial to Henry Collier and his daughters

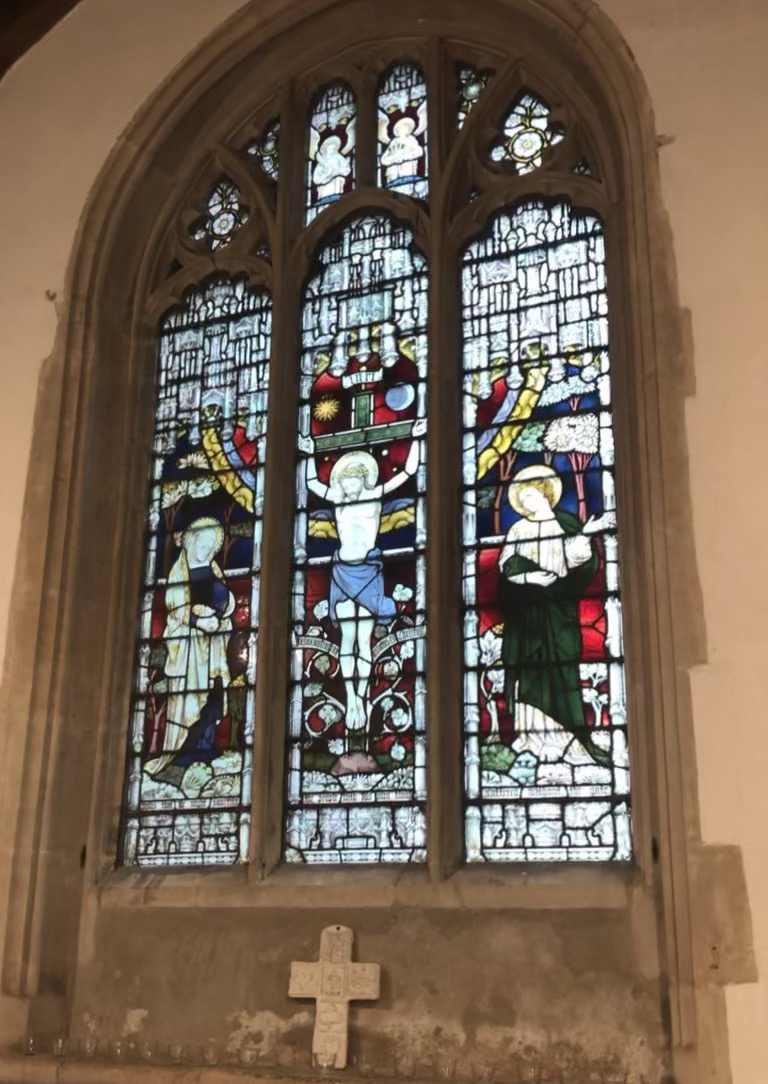

In 1882 a stained glass east window – the main window at the end of the church - was erected as a memorial to Henry Collier and his daughters Ellen and Jane, who both married clergymen and settled in Cumbria and Middlesex respectively.

The Colliers were farmers who over 200 years accumulated more and more plots so that by the mid-19th century they owned a quarter of Stapleford. On his death in 1870 Henry left his land to his son, Henry, a clergyman (d. 1933) and Dr William Collier (d. 1935). Again, there is no evidence of any connection to slavery.

Wealth from plantations?

I did not find anything to suggest that any of the people who have memorials in St Andrew’s benefited from slavery.

But the forebears of two previous parish priests did – and in the next instalment I will take a closer look at the source of family wealth of Revd Robert Hawthorn (parish priest 1845-72) and Revd Frederick Hawes (parish priest 1904-23).

End of the line

After Sir George died, there were four more Dukes of Leeds. In the 20th century they were forced to sell their lands to pay off gambling debts.

The 12th and final duke was Sir Francis D’arcy Godolphin Osborne. A diplomat based in Rome, he helped 4,000 Jews and Allied Soldiers escape the Nazis during World War II.

When he died aged 80 and without issue in 1964, the title the Duke of Leeds became extinct.

A peculiar endnote

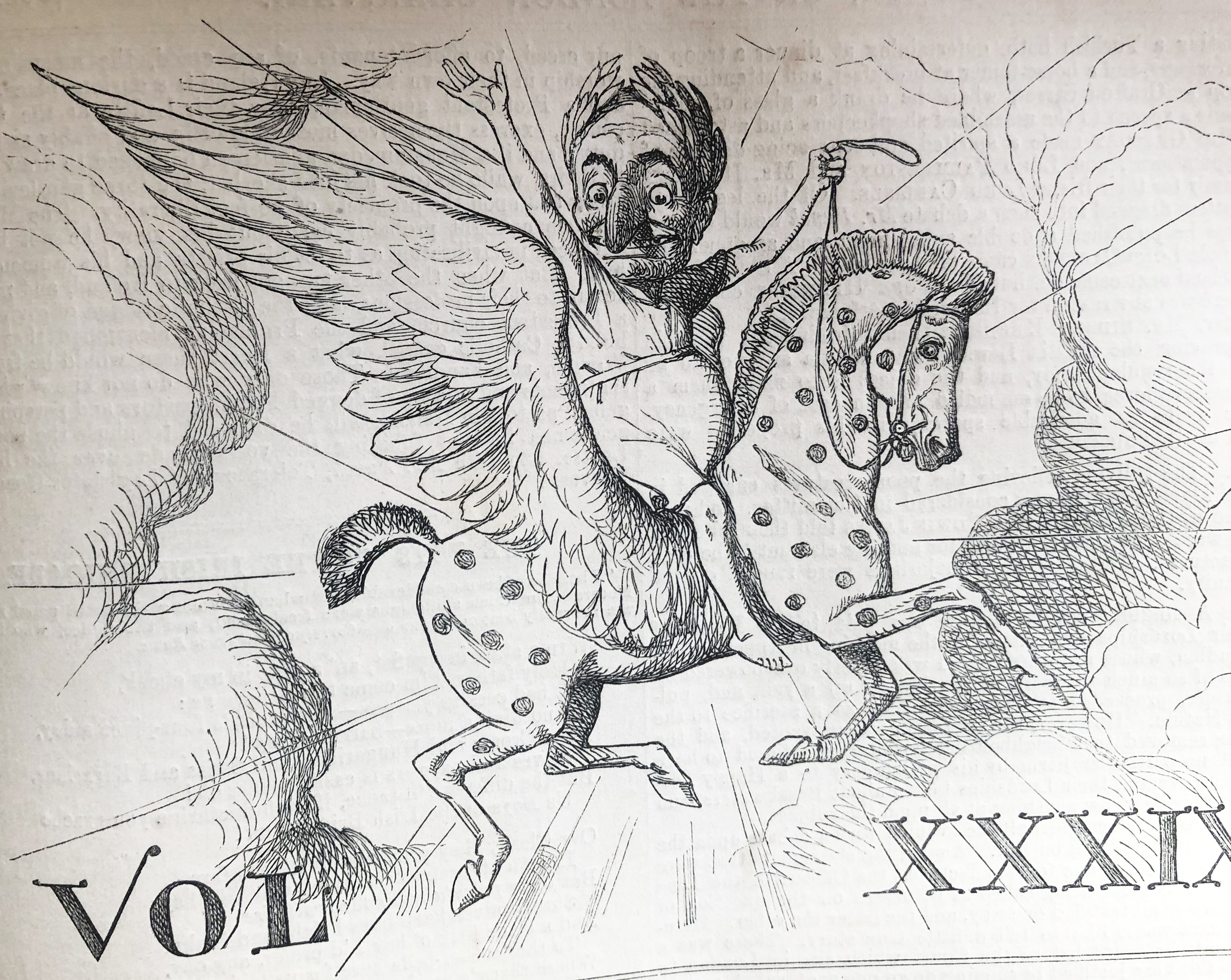

My husband has a compendium of old Punch magazines. He was idly flicking through it when he came across a tiny article from the July 1860 issue, which describes Lord William Godolphin Osborne’s appearance before Cambridge Insolvent Court for debts of £1,066.

Lord William was the son of the 8th Duke whose memorial is in the Lady Chapel. His creditors included tailors, tobacconists and a livery stableman. The son in his defence said that he was 25, had a wife (but no marriage settlement) and that his father gave him an allowance of £100 a year which he refused to increase.

The judge was not sympathetic and sentenced him to six months’ imprisonment.

“Mr Punch” commented that he “knows nothing of the circumstances of this unpleasant story nor why his Grace of Leeds has come to the conclusion that it is more to the credit of his family that Lord Godolphin Osborne should go through incarceration and the insolvent court for such a sum as £1000 than to pay the young Lord’s debts and give him a chance in married life” …

Part 2

Revd Robert Hawthorn: compensated for his role in the slave trade

Last month I looked at the memorials in St Andrew’s to see if these were “contested heritage” – the name given to the memorialisation of people connected with racism and slavery. I concluded they weren’t – but while researching into this I came across a former vicar whose family had owned plantations in Jamaica.

Slavery abolished

In 1833 Parliament finally abolished slavery across the British Empire – 26 years after the abolition of the slave trade.

To appease slave owners, parliament set aside £20 million in compensation. The freed slaves of course received nothing. (To make matters worse, they weren’t even technically free until they had completed up to six years as ‘apprentices’ for their previous owners – more about this later.)

Parliament appointed officials to work out which claimants should receive what. They made a record of every claim and disbursement made – putting values on every man, woman and child that owners claimed as their ‘property’.

Despite the fact that slavery was by now widely condemned and seen as a ‘stain on the nation’, slave owners had no compunction in seeking compensation. Claimants didn’t necessarily have to own a plantation or slaves – they may have been executors or trustees, or owed debts on plantations. This seems to have been the case for Robert Hawthorn, who made a claim on the Penshurst estate in St Ann, Jamaica where he was ‘judgement creditor’ (in other words, entitled to collect the debt owed).

Revd Robert Hawthorn

Robert Hawthorn and his father were born in Jamaica. According to the excellent Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, run by University College London, in 1792 the father Robert Hawthorn owned “83 enslaved people and 48 stock in St Ann, Jamaica”. He died the following year and the estate passed to overseers before being sold in 1823.

In the meantime, the son had moved to Scotland. By 1806, he was apprenticed to a lawyer and by 1818 he had married and was living in Ayrshire. He and his wife Annie Barter Lawrie would have four children. He no longer seems to have any connection with his father’s estate but in 1834 he made a counter-claim for compensation against Gilbert Wm Senior, then tenant for life for the Penshurst plantation, also in St Ann Jamaica. Robert Hawthorn claimed £1,727 but was awarded “interest and accruals only” – or £204 (£24,000 today).

Penshurst became infamous after the publication of former slave James Williams’s Narrative in 1837. Aided by the Quaker Joseph Sturge, who supplied the money for Williams to purchase his freedom, the Narrative detailed the frequent punishments and abuses he experienced while apprenticed to the Senior family: “Apprentices get a great deal more punishment now than they did when they was slaves; the master take spite, and do all he can to hurt them before the free come.”

We may never know what Robert Hawthorn thought about his family’s owning slave plantations or his claims for compensation. If he wrote letters to family and friends that could provide an insight, they are yet to be discovered (if they were kept at all).

Sermons could be another possible source of finding out his views. In the 19th century the sermon offered a great fund-raising opportunity, and provided valuable income for the abolition of slavery and other movements. The Stapleford Chronicle 1770-1899, compiled by Mary Miller, states that during Revd Hawthorn’s incumbency, St Andrew’s invited several guest preachers to raise funds for the Church Missionary Society. Judging by the amounts raised – often more than £500 in today’s money – these were very successful! Have these sermons been lost to history? Or are they lying undiscovered in college archives or personal letters? If Messenger readers have an inkling of where these could be please let me know!

Apology

In last month’s Messenger I said that the family of Revd Frederick William Hawes (St Andrew’s priest from 1904-23) also had connections with the slave trade. Further investigation has shown I was mistaken. His father, grandfather and great-grandfather seem to have been all London-born and -bred. The family wealth seems to have started with Frederick’s father, James Thomas Hawes. Starting out as a pawnbroker, by the 1871 census his occupation was “silversmith” while ten years later the census entry describes him as “silversmith, jeweller and pawnbroker.” (Charles Dickens had earlier written: “the better sort of pawnbroker calls himself a silversmith.”) Whatever his trade, he died a very wealthy man – in his will James Hawes left £12,000, the equivalent today of £1.67m. No wonder Frederick could afford two servants by the time he occupied the Lodge in Stapleford!